Lack of follow-up is the number-one issue that annoys B2B customers, according to a recent study that also says brand promises are trusted by less than one out of five customers.1 This is a plague that internal branding, which aligns employee commitment with the brand promise, must deal with.

And since customer choice is driven universally by trust, confidence, relationships, convenience, ease of doing business, and support,2 managers are compelled to take a closer look at "trust" in their strategic arsenal for brand preference and growth.

Commitments to customers are made on a regular basis by executives, marketers, and customer-facing professionals, such as sales, customer and technical service, and billing. Supplementing sales and service calls as voice of the customer sources may be customer user groups, advisory boards, surveys, and other feedback forums, which are great opportunities to keep abreast of issues that need attention.

But with all these feedback avenues, it's no wonder that lack of follow-up is rampant. As there are two sides to every coin, the flip side of customer input opportunities is the need to manage timely follow-through on customer promises.

Expectations and Communication

Remaining true to one's word is a constant challenge as unexpected issues arise and inevitable dependencies on other internal groups add complexity. One of the keys to managing expectations and fostering trust is to keep customers apprised of progress toward the commitment, providing them with early warning of potential delays. A treasure trove of practical recommendations on the emerging field of promise management can be found in the new book Building Dependability Inc. by Price and Schultz.

Trust is intertwined with our expectations of one another. At the core of expectations is the question of whether our messages in daily conversations are received with the same meaning with which they were sent. "What I told you must have sounded different from what I meant" is all too often the realization among parties when expectations are not met.

Listening skills certainly play a role in the entire process. But more fundamentally, some people intrinsically...

- Are informing communicators while others are directing communicators

- Take initiating roles while others take responding roles

- Focus on control of outcomes or movement toward goals

These three differences in instinctive tendencies form the basis for a huge portion of communication mishaps that erode trust.

The Good News

The good news is that the intersection of these three predispositions offers a bridge for effective communication between any combination of tendencies regarding communication, relationship role, and focus of attention. These obvious, actionable, bridges are introduced by Interaction Bridges,3 which is a practical methodology for on-the-fly adjustments in business environments.

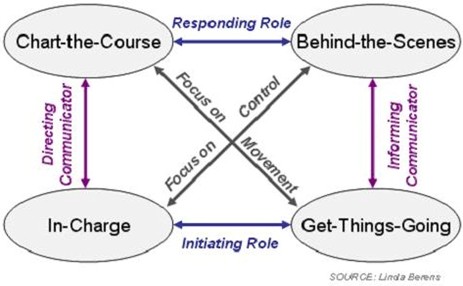

Interaction Bridges is a methodology that helps you avoid the "Be Like Me" syndrome, and it guides you in working from the commonalities you have with your customers' and colleagues' preferences, leading to stronger trust. The easy-to-learn methodology provides practical tools for bridging the gaps between Chart-the-Course, Behind-the-Scenes, In-Charge, or Get-Things-Going styles of interaction. (See Figure 1.)

A Case Study

To demonstrate the use of Interaction Bridges among marketers, Sam (Chart-the-Course) is a business development director for a product division, and Pat (Get-Things-Going) is the division general manager.

Sam is predisposed toward directing, responding and a focus on movement. Pat is predisposed toward informing, initiating, and a focus on movement. Sam's perception of the business development role includes expectations management among external parties, based on the success principle of under-promise and over-deliver. Pat's perception of the general manager role is to take the lead in meetings with customers and potential alliance partners. Pat spends a great deal of time in each meeting laying out the details of proposed programs and explaining the division's rationale for the recommended strategies and tactics. While doing so, Pat stimulates many questions among the parties in attendance; they ask for a number of items, which Pat agrees to provide in the subsequent meeting. Sam's participation includes several comments to keep the discussion on track, making note of the issues discussed as well as the promises made. In truth, Sam would feel more comfortable leading the discussions with backup support from Pat, and Sam makes that suggestion for next week's meeting.

Prior to the next meeting, Sam prepares a reminder sheet of the commitments made, with suggested deadlines for important interim steps. Pat seems overwhelmed to see the list, and comments that it will be a miracle if one or two items is completed this week. Sam overhears Pat chuckling with a colleague, saying "Hey, now I'm getting assignments from Sam!" Sam engages relevant managers in the division to move forward on most of the action items. However, some of the items that Pat mentioned in the meeting are not as familiar to Sam, and as Sam probes for clarification in a pre-meeting with Pat, the pre-meeting is cut short by a call from the engineering director who says there's an urgent challenge to address. Pat rushes to meet with the engineers while Sam goes to the planned meeting with the outside party who request a status report for the promised items, yet Sam is ill-prepared to discuss many of the items. Minutes before the meeting's end, Pat walks in with high energy, sharing new information, addressing some of the promises, and making a few more commitments. Clearly, trust was quickly eroding not only with the customer, but also between Sam and Pat as colleagues.

Figure 1. Interaction Bridges

Three Differences Explained

Let's explore the differences between directing and informing communication styles. Directing communicators are focused on task and time, whereas informing communicators are focused on process and motivation. Accordingly, those who naturally speak in directive communications tend to tell, ask, and urge when they express their thoughts. For instance, Sam may say "Let's take this approach," expecting the other party to either agree or pipe up with an alternative, to address the task in a timely fashion.

On the other hand, those who naturally speak as informing communicators tend to inform, inquire, explain, and describe as they express their thoughts. For example, Pat may say "Here's an interesting approach," expecting to inspire or seek input from the other party, to build involvement in the process, and motivation to act.

As a result, directive communicators are often surprised when people resist what comes across as being told what to do, and informing communicators are often surprised when information they share comes across as non-compelling and is not acted upon. Both parties can have the best of intentions, and yet misread one another. Ultimately, this misreading may lead to inaction, and therefore missed commitments.

Second, the relationship between any two parties is defined by a natural inclination toward initiating or responding roles. Initiating roles exhibit an outgoing, fast pace, while responding roles demonstrate preference for the other party to act first, taking more time, relatively, to reflect before replying. As a result, initiators may be frustrated by lack of feedback, viewing responders as withholding. Likewise, responders may be frustrated at the lack of time to reflect, viewing initiators as intrusive. Again, best intentions can be thwarted as trust in the relationship fades.

Third, the focus of our attention in any interaction may either be control of the outcome or movement toward the goal. Those with a predisposition to focus on control of the outcome tend to monitor information flow, progress, and achievement of the result. Conversely, those predisposed to focus on movement toward the goal tend to create milestones or benchmarks, ask the group for progress reports, and move ahead toward the goal.

As a result, those most interested in control over the outcome are often perceived as stubborn, and those most interested in movement toward the goal are often perceived as rushing to act without considering the end result. This dichotomy of focus also can twist best intentions into a dwindling relationship.

Leveraging Commonalities

By learning to recognize the cues for Interaction Bridges, you can select the predisposition that you share with the other party to find common ground for your interactions:

- Chart-the-Course: directing, responding, and movement

- Behind-the-Scenes: informing, responding, and control

- In-Charge: directing, initiating, and control

- Get-Things-Going: informing, initiating, and movement

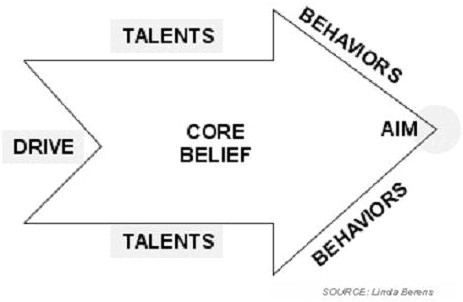

The simple model behind Interaction Bridges makes it both easy to use and very powerful. The essence of each style is clearly explained in terms of its drive, aim, core belief, talents, and attributes. (See Figure 2.) When you understand how to observe the talents and attributes of each personality style, you can adapt as needed the pace, tone, word choice, timing, and quantity of your communications for stronger relationships and trust.

Figure 2. Components of Interaction Bridges

Assume, for example, that Sam's style is Chart-the-Course and Pat's style is Get-Things-Going. The common element in their predispositions is an interest in movement. To build trust, Sam and/or Pat can leverage their shared interest in movement and make adaptations in their natural tendency toward directing/informing and initiating/responding.

Self-discipline on the part of the individual familiar with Interaction Bridges can make all the difference. Interaction Bridges transcends fundamental roadblocks in communication, expectations, and trust, greatly improving the probability of keeping promises to customers and colleagues.

Case Study Solution

What should Sam do to improve the likelihood of keeping customer promises? Knowing Interaction Bridges, Sam should realize that Pat is acting upon the Get-Things-Goings natural tendencies to inform, initiate, and keep things moving. It's very important to Pat that all the parties in a group feel consensus and inspiration toward common goals. In the initial meeting Pat interpreted Sam's slight pauses as a sign of discomfort in leading the discussion, whereas Sam was simply behaving in the responding role natural to Chart-the-Course style. Sam's inclination to provide a reminder sheet and suggested milestones comes across to Pat as a mild form of insubordination. In the pre-meeting, Sam's statements of fact are interpreted by Pat as non-supportive of the division as a working group. Instead, Pat would prefer to hear Sam make suggestions that reflect colleagues' interests. Pat is enticed by the engineers' dilemma, and allows that issue to take precedence over the external meeting due to the allure of exploring options, and due to Sam's desire to lead the meeting discussion with the outside party.

For success, Sam should build from common ground with Pat's shared focus on keeping things moving. As soon as possible after each meeting, Sam should engage Pat in assembling and communicating the action item list and milestones. In the common interest of keeping things moving, Sam should ask Pat for input on strategies to keep the momentum manageable and jointly decide what incremental portions of information are prudent to share in the expected series of meetings with the outside party. Sam should suggest involving colleagues whenever appropriate, to address Pat's desire to be inclusive. By engaging Pat in this prompt post-meeting discussion, Pat will be more excited to be on time to the subsequent meeting and keep things moving. Interaction Bridges is a valuable tool for Sam in addressing what otherwise would be a disastrous experience in keeping customer promises.

If trust is a key driver of customer choice, and lack of follow-up is the number one issue that annoys buyers, as research substantiates, then commitments must be carefully managed through effective tools and best practices.

In his article "Introducing the Chief Listening Officer," David Jackson writes, "Companies that can earn and retain a customer's trust will be in a privileged position. They will have the edge in selling to that customer."4 By addressing fundamental obstacles in building trust with others, Interaction Bridges is a strategic tool for keeping customer promises.

*Note: The Interaction Styles Model is the property of Linda V. Berens and cannot be used, duplicated, or disclosed without the express permission of Telos Publications. Linda Berens is a well-known expert in Keirsey's Temperament Theory and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. "Be Like Me" Syndrome was developed by Sue A. Cooper, Ph.D. The four Interaction Styles can be overlaid on the four Temperaments to create the 16 MBTI Types.

Understanding Yourself and Others, In-Charge, Get-Things-Going, Chart-the-Course, and Behind-the-Scenes are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Unite Media Group, Inc.

Endnotes:

- "The World is a Web of Promises" by Reg Price, managepromises.com, 2005.

- Return on Customer, by Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, 2005.

- Understanding Yourself and Others: An Introduction to Interaction Styles, Telos Publications, by Linda V. Berens, 2001.

- "Introducing the Chief Listening Officer" by David Jackson, CRMGuru.com, 11/18/05.