The marketer in question is, of course, David Ogilvy. He was given the educational opportunity of a lifetime—the chance to study at the prestigious University of Oxford. He was expelled, with the reason undisclosed, in 1931.

Ogilvy never had a college degree, proving you don't need to have a marketing degree to be a fantastic marketer. However, the experiences in the years that followed did shape him into one of the greatest marketers ever.

The Wilderness Years

After a brief stint as a kitchen monkey in a Paris hotel, Ogilvy started working for the Aga Cookers company in England, selling stoves door to door. It was his first taste of marketing, and he excelled, eventually writing a sales manual for Aga salesmen described by Forbes as "probably the best sales manual ever written."

After fortuitously landing a job at a London agency in part because of that very manual, in 1938 Ogilvy was sent, at his request, to the United States to attend George Gallup's Audience Research Institute in New Jersey. He cited this experience as a huge influence on his thinking, because he learned not only research methods but also how to apply findings to real life.

In the 10 years that followed, Ogilvy worked for British Intelligence during the World War. He purchased farmland in rural Pennsylvania, where he lived among the Amish. By 1948 he realized that farming wasn't his calling, and he moved to New York to start his own ad agency.

Founding an Agency

Ogilvy became a founding member of Hewitt, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather (which would eventually become Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide), even though he had little experience as an ad man.

But after writing ads for such companies as Lever Brothers, General Foods, American Express, and Shell, Ogilvy soon became one of the most prominent figures in the world of advertising. Ogilvy on his successful ad copy: "They made Ogilvy & Mather so hot that getting clients was like shooting fish in a barrel."

Five of Ogilvy's Most Important Marketing Lessons

1. "Unless your advertising contains a big idea, it will pass like a ship in the night. I doubt if more than one campaign in a hundred contains a big idea."

If a marketing campaign is unsuccessful, it's likely because it lacks ambition and creativity. Ogilvy's thinking was that in a world of average you needed to cut through mediocrity with a big idea that captured people's attention.

Don't confuse the notion of a big idea with the loudest or most controversial idea, however; a big idea means seeing something no one else doing yet being brave enough to do it yourself. It's not about creating a wacky idea, but it is about doing something different and making it successful.

2. "In the modern world of business, it is useless to be a creative, original thinker unless you can also sell what you create."

This lesson may seem to contradict the first lesson, but the point is that you should never be creative merely for the sake of being creative; you should only be creative to achieve the most important thing as a marketer: sales.

Moreover, creativity does not automatically equate to better sales; how you apply that creativity is most important.

3. "I abhor advertising that is blatant, dull, or dishonest. Agencies which transgress this principle are not widely respected."

A lot of people will ponder whether this is a marketing lesson or a moral lesson. It definitely has elements of both. First, Ogilvy wanted his ads to carry integrity; he wasn't looking for short-term exposure that would lead to long-term pain either for his clients or his agency.

Whether it was a legacy or reputation that Ogilvy was trying to build, he wanted to create ad copy that would be respected and admired for a hundred years; he always had branding and his own image in mind.

4. "Advertising people who ignore research are as dangerous as generals who ignore decodes of enemy signals."

Ogilvy was not a marketer who trusted his success to luck; he did not base his ideas on gut feeling or random thought. He was scrupulous and thorough in his research, which he would use to ensure his ads reached and convinced their audiences.

After attending George Gallup's Audience Research Institute, he became a stickler for research and testing. It was not good enough for an ad to be successful; he had to know exactly why it was successful so he could take note for other ads.

5. "If we hire people who are smaller than we are, we will become a company of dwarfs. If we hire people who are larger than we are, we'll become a company of giants."

This is another lesson that epitomizes Ogilvy. He was not ego-driven; he didn't want to build an advertising agency with zealots, followers, and supporters. He wanted to hire people with the values he shared, but they had to be as good or better than those already working for him.

He was a huge believer in the value of community within a company; he was unreserved in his desire to help his employees and ensure their happiness (both at work and at home), believing that a happy worker was a good worker, in the simplest terms.

But Ogilvy wasn't soft. In giving everything to his employees, he expected the same back in their work. His ethos was, If I give you the resources and help, to be a giant in marketing, then you had better show me you're a giant. There was no sentimentality.

Notable Ads by Ogilvy

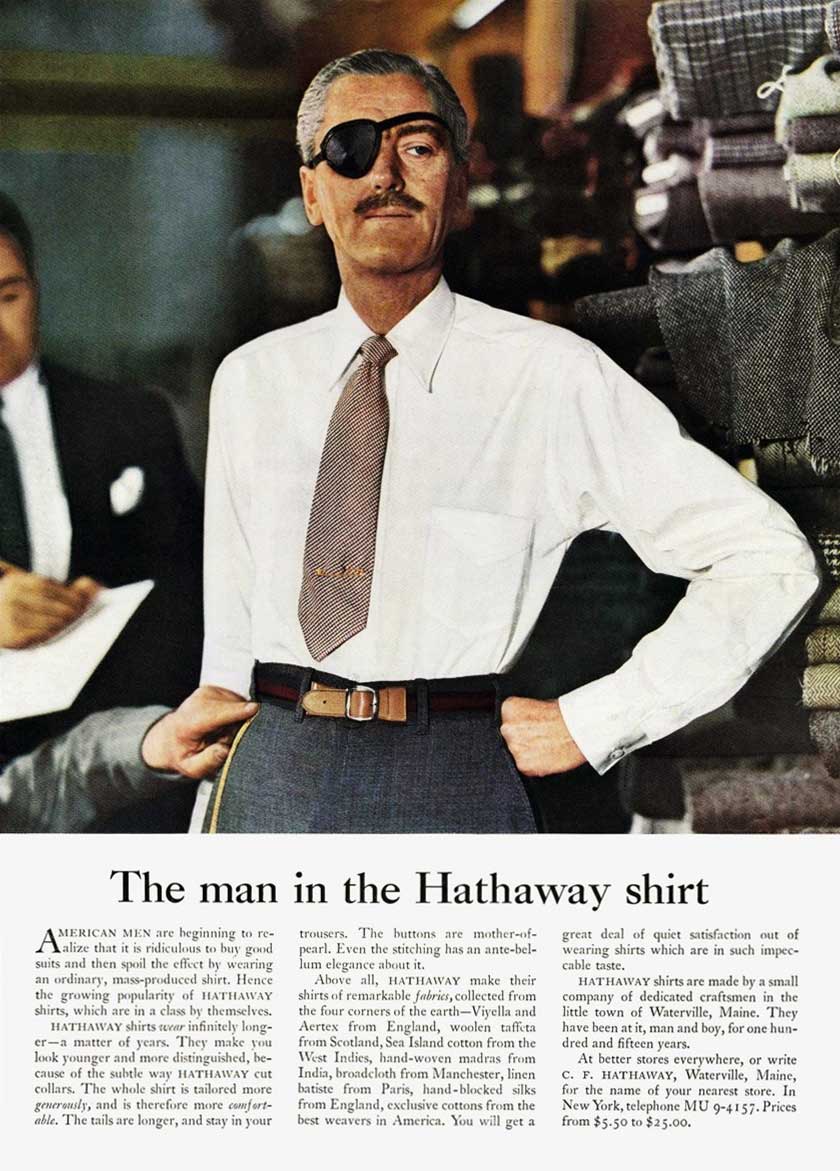

Hathaway Shirts

Read the ad copy and then tell me why the man has an eye patch. A cinematic rule called Chekhov's gun can be applied here; it states that a prominent object in the first act should be used in the last act.

In this example, the first thing that most people notice is the eye patch, and it is not unreasonable to expect to find the reason behind the man's having an eye patch. However, the eye patch is simply a red herring, a visual draw to create curiosity.

By defying the rule of Chekhov's gun, you can gain the audience's attention and simultaneously create hype around the ad: Why does the man have an eye patch? This sort of clever subtlety is why David Ogilvy is revered as a marketing genius.

Schweppes

The mark of a great marketing campaign is how long it runs, proving that it both works and stands the test of time. This is one of a series of Schweppes ads that ran during the 1960s and 1970s.

These ads perfected the use of a narrator character, someone who seemingly isn't part of the scene yet whose interactions are absolutely key. If you look at these ads, then look at the famous Old Spice ads, you'll notice a lot of similarities.

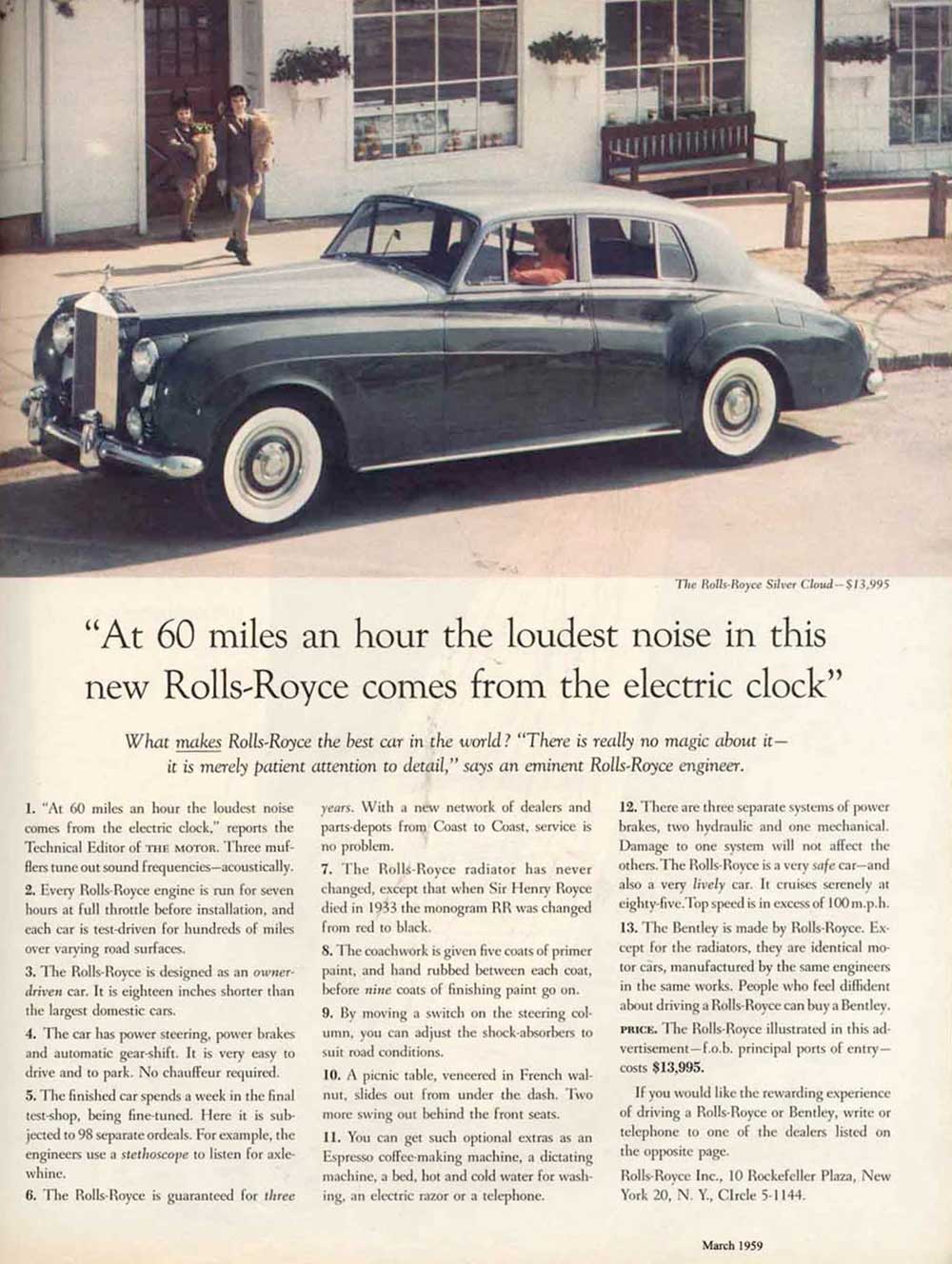

Rolls-Royce

Proof, if any was needed, that the headline is 90% of ad copy. If you can't get that right, then you won't draw in the audience, which makes the rest of your copy completely redundant.

"At 60 miles an hour the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock" is often cited as the greatest ad headline of all time; it shows fantastic understanding of an audience searching for a vehicle that provides ultimate luxury.

Today, the only impressive thing about this headline might be that alludes to a quiet car, but back in 1958, when this ad was published, an electric clock in a car was pretty swish, too; sewing those two points together seamlessly shows the brilliance of Ogilvy.

Even the subtlety of using the word "noise" is fantastic. You could use "sound" instead of "noise"—they both mean the same thing—but "noise" connotes a problem, an irritant... yet that minor ticking is anything but noise, really. So, without missing a beat, readers create an image in their head of a relaxed, serene driving experience free of irritation and stress.